Creating Superpowered Teeth

New Research in Touro College of Pharmacy’s Labs Showcases Possibilities of Microbial Oral Transplants Fighting off Diseases

Imagine if your dentures could fight off the flu, or your dental crowns could help protect your lungs. That idea —farfetched as it might seem— is the premise behind a line of research underway in the laboratory of Dr. Zvi Loewy at Touro College of Pharmacy. The work, which began with a pharmacy student and continued across several schools within Touro University, asks a deceptively simple question: can the oral cavity be engineered to defend itself against harmful pathogens, not with antibiotics, but with beneficial bacteria that already exist in the human body?

The research draws its rationale from an established medical practice. In patients with severe gastrointestinal inflammation, fecal microbial transplants from healthy donors have been shown to restore microbial balance and resolve symptoms. Dr. Loewy wondered whether a similar principle could apply to the mouth. People constantly swallow and inhale microorganisms from the oral cavity, he explained, and some of those pathogens can travel into the respiratory system and contribute to serious disease. The question, then, was whether pathogenic microorganisms in the mouth could be displaced by commensal bacteria before they have a chance to cause harm elsewhere in the body.

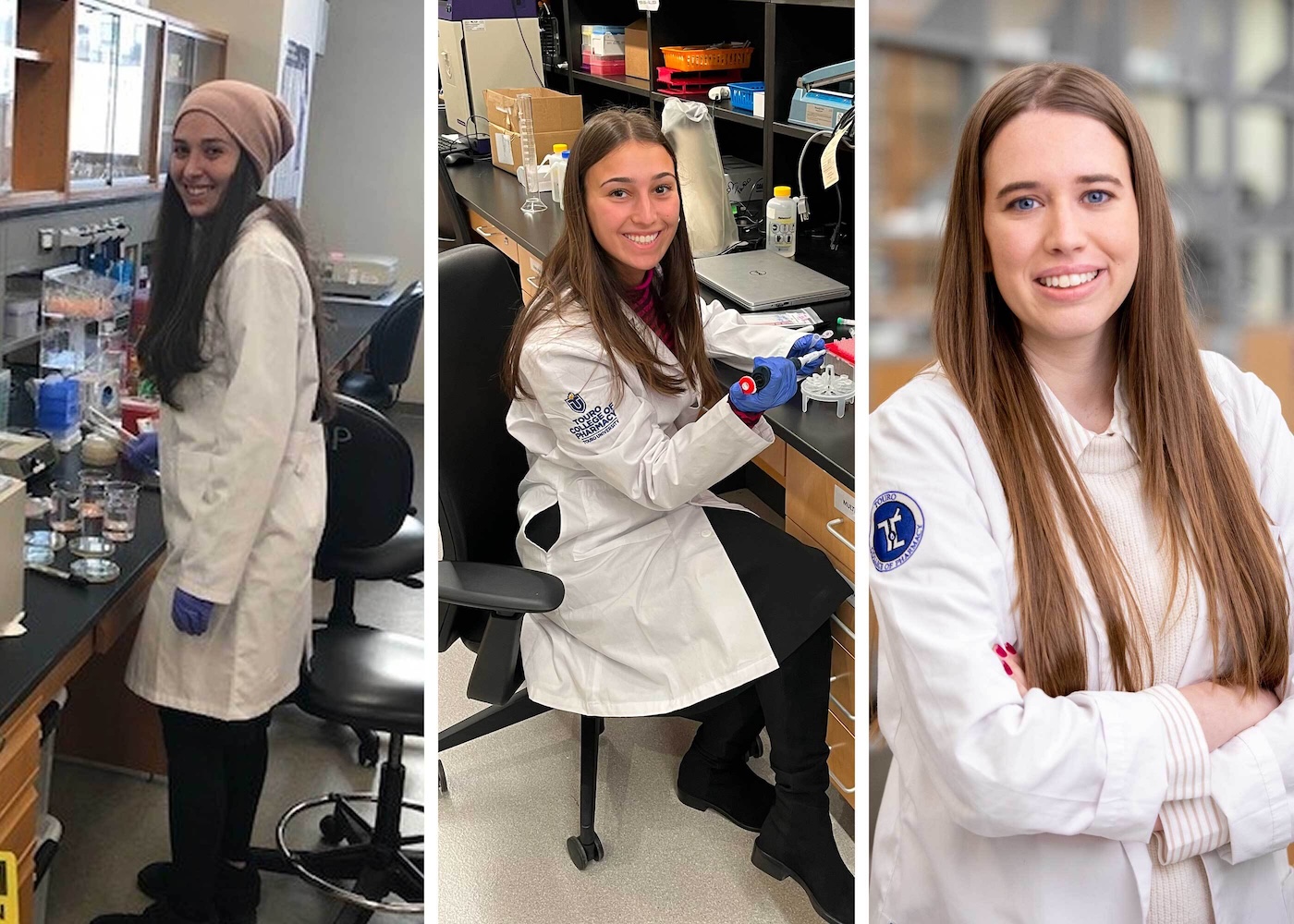

That question became the basis for a multi-year collaboration involving students at different stages of their academic careers. The project was initiated by Irene Berger, a 2023 graduate of Touro College of Pharmacy, and later carried forward by Shira Nahon, a graduate of Lander College for Women, now a first-year student at Touro College of Dental Medicine, along with Shalva Goldenhersh, a current undergraduate at Lander College for Women. Together, they focused on dental materials as a testing ground, using laboratory model systems that included dentures, dental crowns, veneers, and hydroxyapatite, the mineral that closely mimics natural tooth enamel.

Berger, one of the first students on TCOP’s specialized research track, said that she had been attracted to TCOP because of the school’s focus on research. “The goal of our project was incredibly broad: find an alternative approach to fighting infectious diseases without conventional antibiotics,” said Dr. Berger. “I really liked the idea of being involved in something targeting infectious diseases.”

In the lab, the team examined how oral and respiratory pathogens adhere to these materials, with particular attention to Haemophilus influenzae, a respiratory pathogen known to exacerbate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the third-leading causes of death worldwide. What they found, according to Loewy, was that molecules secreted by commensal bacteria could interfere with the bacteria’s growth process. The beneficial bacteria outcompeted the pathogens, preventing H. influenzae from binding to dental surfaces. The effect was consistent across a range of materials, from denture acrylic to porcelain crowns to enamel-like hydroxyapatite, suggesting that the phenomenon was not limited to a single dental surface or product.

For Berger, the work was driven by a desire to explore alternatives to conventional antibiotics, particularly in the context of respiratory disease. She focused on testing commensal bacteria against Haemophilus influenzae and later against Pseudomonas species, pathogens commonly found in patients with COPD who experience recurrent respiratory infections. The experiments showed that the probiotic inhibited pathogen growth in a way that was both dose-dependent and time-dependent. While the team could not determine definitively whether the bacteria were killing the pathogens or merely suppressing their growth, the results offered viable non-antibiotic strategy for reducing pathogen load.

The team explored different incubation strategies, including introducing beneficial bacteria before exposing surfaces to pathogens, as well as co-culturing at the same time. While both approaches showed promise, establishing the commensal bacteria first appeared to be more effective. Nahon said the work reinforced the idea that oral health cannot be separated from overall health, particularly given the role these pathogens can play in worsening systemic disease.

“Our goal is not just to have a healthier mouth, but a healthier body overall,” said Nahon. “Part of the research that excited me the most was realizing that our research might help a vast number of people—not only those in the dental chair.”

The implications of the research continue to unfold. Rather than treating infections after they occur, the work points toward preventive strategies embedded directly into dental materials or oral care products — approaches that could reduce reliance on antibiotics and limit the spread of harmful pathogens beyond the mouth. For Loewy and his students, the scope of the question remains deliberately open-ended, with the possibility that something as routine as a denture or crown could one day play a role in protecting not just oral health, but overall health as well.