News

In the ER “Every Week, Learning Something New”

Touro Pharmacy Doc in the Trenches During COVID-19 Pandemic Looking for New Solutions

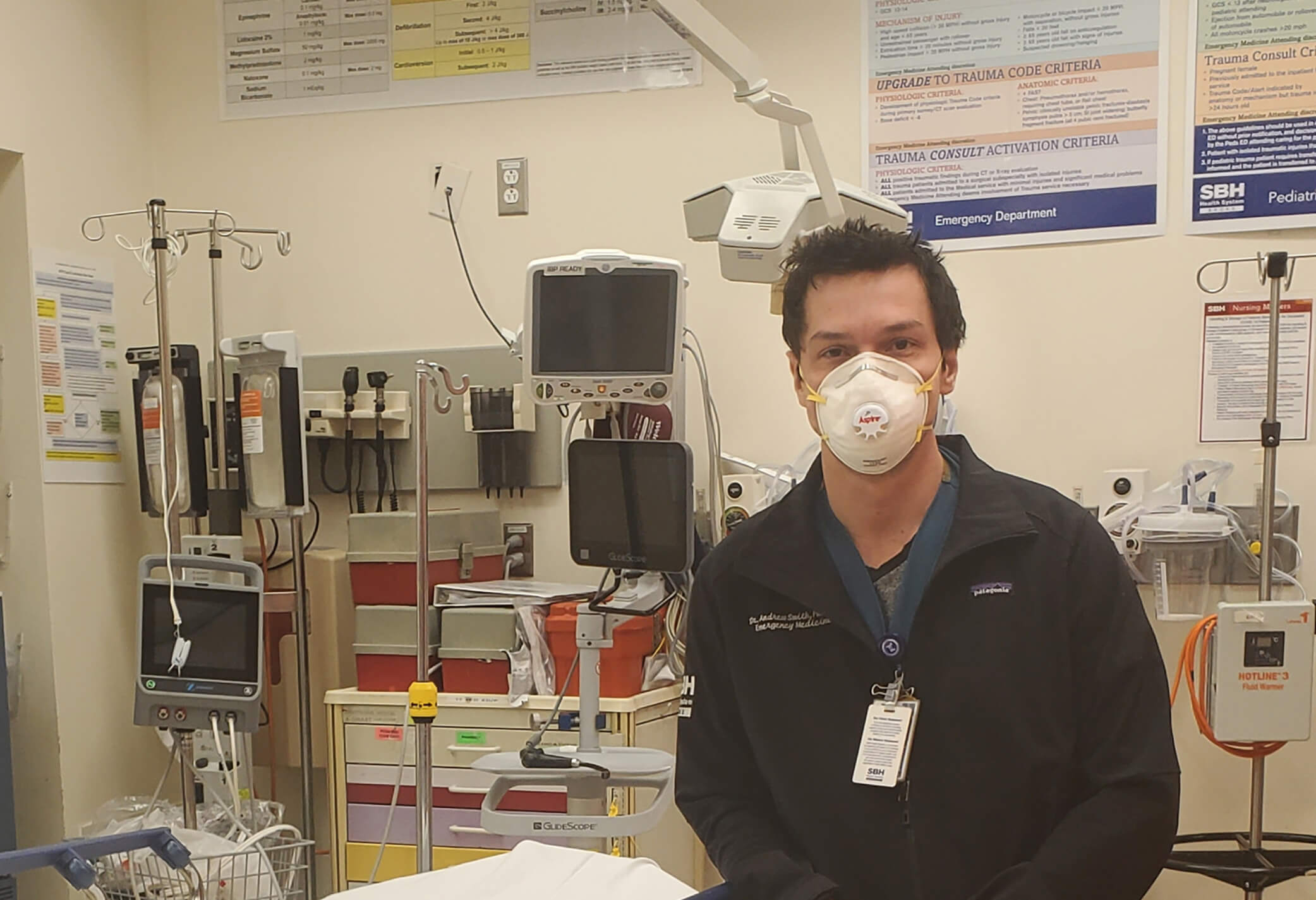

Andrew Smith, PharmD, is assistant professor of pharmacy practice at Touro College of Pharmacy, and postgraduate year two (PGY-2) emergency medicine residency program director at St. Barnabas Health System hospital in the Bronx. He’s been on the front lines in the Emergency Department (ED) during the pandemic, providing bedside care and making sure that intubations and sedation of patients take place in the safest and most effective manner.

What is your role in the ER during the crisis? What has been your daily reality - or is every day different?

We have had to take on new roles due to problems with the medication supply chain, and increased numbers of patients needing ventilators, and thus painkillers and sedation. Many medications we prefer to use have been running out, so every day we have to discuss with providers new alternatives. Currently, the volume of patients is slowing down due to the NYS-PAUSE order of Governor Cuomo. During the peak, we had up to 30 patients intubated in the ED, despite increasing our ICU capacity from 16 to over 40 beds. We were completely overrun. On average, we had two to three patients expiring in the ED daily, which certainly was something new to many of us. Previously, this sometimes happened on a single shift, but not daily and for weeks. Managing that many ICU-level patients in the ED was not the norm either, and we had to step up as a pharmacy team to help nursing with sedation of these patients and adjusting their medication, as COVID-19 patients generally need higher levels of painkillers than the average patient having respiratory failure.

Experts keep saying there's still a lot we don't know about the virus and so it's impossible to make accurate predictions how things will evolve. Do you agree?

Every week we are learning something new. At first, we were treating these patients just like we treat our average patients with respiratory failure, and if clinically appropriate, treating acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients - potentially adding hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in select cases. Then, we identified possible Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS), an acute systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by fever and multiple organ dysfunction, as a secondary problem and started prescribing medication to lessen severe damage to lung tissue caused by the CRS. In just the past two weeks we identified patients who needed medication to prevent blood clots from forming. Now VA data is showing that hydroxychloroquine, used to treat autoimmune conditions, likely provides no benefit to patients with COVID-19 and the dangers it presents for heart damage are likely more serious than we previously anticipated. So, we learn something new every week, and hopefully people quickly realize the importance of doing double-blind randomized trials rather than making desperate attempts with therapy that may provide no benefit and even harm patients.

How do you deal with the pressure and uncertainty when there's currently no proven drug regime or treatment that seems to work?

It’s certainly frustrating as a provider, but there are many disease states where we have no cure or preventative strategies, and we simply do our best with supportive care. There are theoretical therapies, but we need to do proper trials to evaluate these rather than blindly throw therapies at random patients without logging data for future evaluation. Supportive care is the best we have right now, as well as enrolling qualified patients in the proper clinical trials.

What's been the biggest challenge?

So far it’s been managing the amount of misinformation and rescue therapies that have no role outside of clinical trials. Many providers are caring for patients that may be outside of their comfort zone, and they are reading abstracts without evaluating the data and extrapolating it to their patients. For example, there’s no sound data supporting the use of vitamin D and ascorbic acid for COVID-19, yet some providers still give it to patients. Ascorbic acid has been proven in large randomized multi-site clinical trials to be of no benefit. As providers, we need to remain objective and make decisions based on quality data from studies done in test tubes rather than on humans.

Can you share some of the bright spots?

This has really shown New York State and the country how woeful and inadequate our preparation was for this virus, and I think that we are going to be more prepared for the next pandemic or the next crisis. The tremendous amount of community support from food vendors and others for the healthcare teams has been fantastic, as well.

What in your training is proving to be helpful on the job?

Despite my training being in emergency medicine at Maimonides Medical Center, my first job was as an ICU specialist at BronxCare Health System. There, I learned about pulmonary complications, ventilator management, moving patients into prone positions for ventilation and oxygenation. This has translated to a much greater understanding of airway pharmacology, which is something I am passionate about both in teaching and for future research.