News

Touro in Haiti: Learning to Communicate with Patients in a 3rd world Country

By Khloe Le, PharmD Student, Class of 2017, Touro College of Pharmacy

As a pharmacy student, I was fortunate to go on a medical mission to Haiti this past June to help the underserved in need of medicine and medical aid.

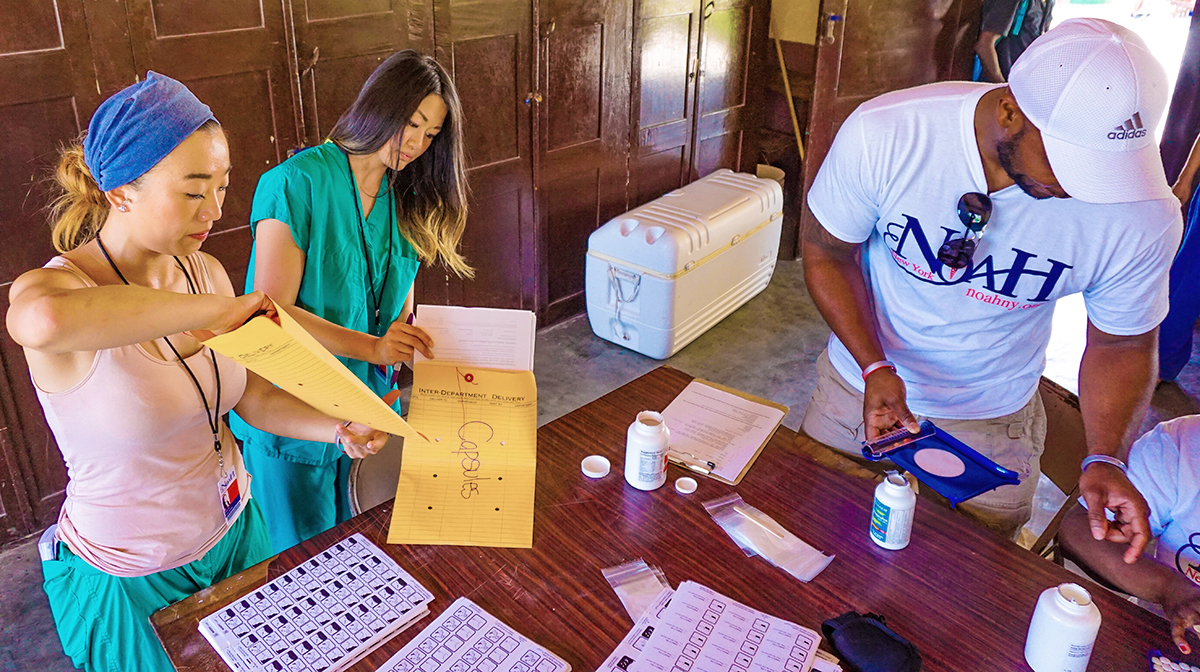

Led by Dr. Roopali Sharma, Associate Dean of Assessment, and along with fellow Touro College of Pharmacy student, Phoebe Wong, and resident Rebecca Fletcher, we set up a clinic in a school and filled 400 prescriptions a day.

I hold the medicine up and start to pat my tummy, and then pat their tummy. This medicine is for your stomach. My translator repeats back in Creole. I point to the pictogram label and tell them take one tablet once a day. I point to each picture, and show the actual tablet to the patient and demonstrate a motion of taking the tablet into my mouth. The translator repeats back in Creole only to tell me that the patient says there is no need to translate. I tell the patient to take this with no food while shaking my head no, and then I go through the motions of pretending to eat. The translator repeats back again, and once again the patient says that they completely understand the message I am trying to get across.

My translator tells me the patients like the direct interaction and that they can understand what I am trying to communicate. The patients can tell that I really care about them and I want to make sure they know how to take their medications. At that moment I come to a realization: although I do not speak Creole, they understand what I am saying through my eye contact, my body language, and the pictograms.

Going into this trip I realized that there would be barriers we would have to overcome. Many Haitians are not able to read Creole. Therefore, they are unable to understand medication labels even when printed in Creole. Additionally, there may be limited access to a translator. After many hours of research, I came across a software program created by the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) titled PictoRx designed to relay pharmacy information through pictograms. The program can create labels, story boards, instruction sheets, and medication calendars. However, generating these labels in remote villages in Haiti could prove to be problematic. Our solution was to preprint labels utilizing the approved pictogram images and carry these labels to Haiti.

I found that counseling patients with pictograms worked to our advantage. We were successfully able to explain to patients how to take their medications. When I was in Kenya teaching deaf children, I learned that nonverbal communication can be a very powerful tool. Communication comes in all shapes and forms. Essentially, the end goal of communication is to understand an idea. The experience that I had in Haiti was unforgettable, and I found it rewarding to travel to remote villages and provide medical care in a place where there is barely access to healthcare.